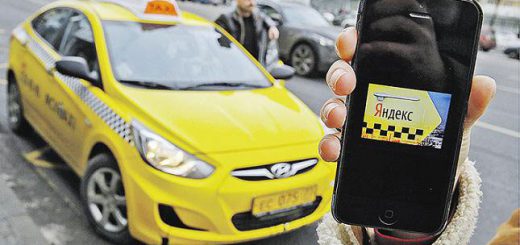

Yandex, Russia’s search engine’s car-hailing app fights to retain dominance of $7bn market and stay ahead of competitors like Gett and Uber. Five years ago, reports the Financial Times, Yandex launched a taxi-hailing app, which quickly came to dominate the city’s taxi market. Last month, however, it cut its minimum base fares in half, to Rbs99 ($1.60) — making it cheaper than Moscow’s public transport for some trips — in an aggressive bid to counter rival car app providers Uber and Gett.

And this willingness to adopt heavily subsidised prices highlights not only the financial squeeze being put on Moscow’s taxi drivers, but also how hard Yandex will fight to retain its grip on a Russian taxi market that the government values at Rbs441bn, after growth of 85 per cent in the past five years. With a two-year head start on Uber, which came to Russia in 2013, Yandex Taxi now accounts for about 55 per cent of all taxi rides in Moscow, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

“We are still the market leader,” says Yandex Taxi’s chief executive Tigran Khudaverdyan. “I don’t see how anyone could beat us.” Uber of the US and Gett of Israel are still trying, though. Together, they account for about half of the remaining 45 per cent of rides in the city, with the remainder going to taxis ordered by phone or hailed illegally, says Bogdan Konoshenko, a Moscow taxi company owner and member of the city’s chamber of commerce.

Until the taxi apps came to Russia, cabs hailed illegally on the street were the norm. Their drivers — many of whom came to Moscow from former Soviet states in the Caucasus and Central Asia — were notorious for having only a rudimentary knowledge of the city and the Russian language. Mr Khudaverdyan says that when Yandex Taxi was launched, illegal rides made up “80 to 90 per cent” of the market — creating an opportunity for a superior app-based service “Basically nobody else was doing it,” he says. “Public transport is of a very low standard. People are poorer, so they have fewer cars. The climate is terrible.”

Yandex Taxi’s model is different from that of Uber, as it does not operate its own fleet of cars, or employ individual drivers as contractors. Instead it works with independent taxi companies, giving it 60,000 drivers in Moscow alone — but unites them under the powerful brand name it has built through its Russian language web search business. This has even proved strong enough to stave off competition from Google.

“There’s no other car-hailing application on the planet which is backed by a search engine,” notes César Tiron, an analyst at BofA. “They definitely have a branding lead.” They also claim to have a higher standard of drivers, as they require candidates to score 80 per cent on a poetry-based Russian language test.

“Our drivers are civilised,” explains Mr Khudaverdyan. In 2015, revenues from the car hailing division, which Yandex spun off from its main business last year, grew 201 per cent year on year, and up by nearly 175 per cent this year.

Yandex’s market dominance has left Uber with an uphill battle. To fight back, the $68bn-valued San Francisco tech group — which is backed by several Russian olicharchs and the country’s largest state-run bank — has been undercutting Yandex on price and bringing in drivers formerly from the unlicensed sector. It expects to be up and running in as many as 20 Russian cities by the end of the year. “Taxis used to be a luxury, and now they’re an add-on to public transport,” Dmitri Izmailov, head of Uber’s Russian operations, told the Financial Times.

Mr Izmailov has even developed a cash payment option for Russia — the only one Uber operates in the world — and is working on a local version of food delivery spin-off UberEats. He expects it to be popular in Moscow, where most pizza delivery services quote a wait of an hour and a half. Uber has also escaped the threat of a ban from city authorities, after agreeing to use only licensed drivers and share ride data with city authorities.

But this has done little to dampen the ire of Moscow’s taxi drivers, who went on strike last month to protest about the Uber-Yandex price war to demand greater regulation of taxis in the city. Mr Konoshenko complains that many drivers still ignore Moscow’s standardised taxi requirements — painting cars yellow and applying for yellow licence plates — which can cost up to Rbs100,000 a car. “It’s hard to compete with people who aren’t paying the same expenses as legal taxi drivers,” he says. “Most taxi companies are running losses; only five or six are still buying new cars.”